Analysis: Why a Djibouti-led mission’s report on Somalia-Kenya diplomatic row blew up in President Guelleh’s face

For Djibouti President Guelleh, the IGAD mission was a way to get back at President Farmajo.

By The Star Staff Writer

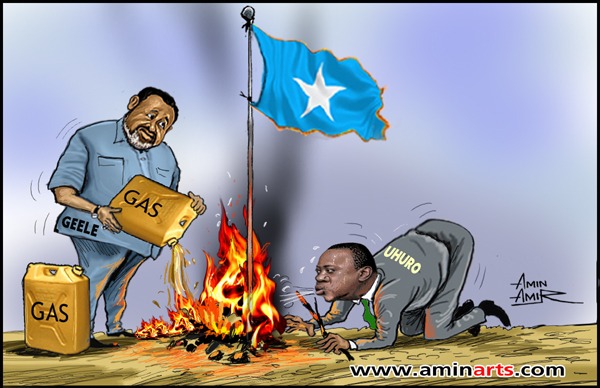

MOGADISHU – Last month’s report by an eight-nation bloc in East Africa on the diplomatic row between Somalia and Kenya had all the ingredients that could make it go over like a lead balloon with Somalia — but not with Kenya, whose violations in and against Somalia were openly defended or excused, and Djibouti, whose president used it as a cudgel to get back at his Somali counterpart for restoring diplomatic ties with Eritrea, Djibouti’s arch foe.

The report was a missed opportunity to boost the regional peace and resolve the escalating diplomatic tension between Somalia and Kenya. It has added fuel to the fires in the Horn of Africa region, setting off a fresh diplomatic row between Somalia and Djibouti.

By employing half-truths, outright lies, irrelevant information and cover-ups, the report’s conclusions read like a shabby attempt to mislead the world and blatantly create excuses for Kenya’s violations of Somalia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.

Terming it “baseless” and “partial,” the Somali government said the report contained “clear inferences that the government of Kenya wholly influenced” its content.

The report’s simplistic, biased and poorly written conclusions underscored its writers’ cavalier attitude toward Somalia’s complaints and their lack of appropriate seriousness during their investigation.

In Somalia, for instance, the Djibouti-led team met with only two low-level Somali officials: A state minister and an unnamed deputy minister, as well as the United Nations’ Envoy for Somalia James Swan and an African Union official Simon Molingo. In Kenya, it met with two ministers — foreign affairs and defense — the army chief and Kenya’s Africa bilateral director. Kenya’s ambassadors to Djibouti and Somalia also attended the mission’s meeting with Kenyan officials.

The objective of the regional mission was to verify the Somali government’s allegations that a Kenyan-backed, anti-Somalia militia is operating inside Kenya’s territory. Mogadishu conditioned any resumption of diplomatic relations with Nairobi on the militia’s withdrawal, a demand that forced the leaders of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development, or IGAD, to order an investigation into the matter in their extraordinary summit in Djibouti on Dec. 20. Djibouti President Ismail Omer Gulleh was mandated to name the seven-member team that was to carry out the verification.

But, except for one, the team’s report trivialized the gravity of Somalia’s main grievances, which were: Kenya’s recognition and collaboration with the Kismayo chief Ahmed Mohamed Islam “Madobe”, creating, training and maintaining on the Kenyan soil an armed group under the leadership of now-fugitive Abdirashid Janan, Kenyan army’s participation in the illegal sugar and charcoal trade in Kismayo and the violation of Somalia’s land by Kenyan forces under the African Union Mission, or AMISOM. The report confirmed Kenya’s violation of Somalia’s airspace.

“Kenyan aircraft entered the Somali territory in disregard of the provisions of the Convention on Civil Aviation signed in Chicago on 7 December 1944,” said the report.

But on the other allegations, the team — six Djiboutian diplomats and military officers and an IGAD representative — elected to gaslight the world by introducing irrelevant issues, such as the legality of forming a local force for a Somali regional administration and Somalia’s ban of khat, a Kenyan stimulant leaf. The report falsely dubbed Janan’s militia that is being fed, lodged and protected by the Kenyan army in Kenyan army camps as “intruders” deposed by Somalia’s federal army.

“Therefore, the commission can affirm that on the day of its visit, it located them (Janan’s militias) inside the Somali territory,” the report wrongly claimed. “To preserve the security of this defeated force, the commission refrains from revealing their exact location.”

The truth is the Kenyan army moved Janan’s militia from its position near the border to an army base inside Kenya to hide it there before returning it to its earlier base near the border, where on Dec. 25 it waged a war against the Somali army in the border town of Belet Hawo, which resulted in the death of 14 civilians, among them women and five children from the same family.

Djibouti defended the team’s work.

“With regards to the way the mission was fulfilled, there is no doubt that it was carried out with professionalism and impartiality,” said Djibouti’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation in a statement.

The statement also tried to clear Djibouti of any accusation of bias.

“While remaining strictly neutral, the Republic of Djibouti was driven by the sole purpose to help the two sisterly nations ease tensions between them and has adopted an unbiased approach based on strict objectivity.”

A former Kenyan senator from Mandera county, where Janan’s militia is based, laughed off Djibouti’s claims.

“If the Djibouti team that visited Mandera report that they did not see Janan’s militia in the town, they probably had wool over their eyes rather than face masks,” he tweeted.

In fact, the IGAD mission failed to seek independent sources or witnesses to verify the Somali allegations against Kenya, which invaded Somalia in 2011 before later joining the African Union peacekeepers. The mission also ignored the publicly available hard evidence, such as the widely shared videos of Mandera county residents and their lawmakers, complaining about the threat that Janan’s presence poses to the security of their county.

During its visit to Mandera, the regional mission failed to have an audience with Mandera county officials and residents to learn more about what is happening in their region. Instead, it blindly justified Kenya’s violation of Somalia’s sovereignty.

No one “can contest the proximity of the Kenyan government to the (Somali) regional authorities to preserve security on their soil in a region infested by terrorists,” the Djibouti-led team concluded. “Kenya has made great human sacrifices to free this (Somali) region from the shebabs (sic) in order to protect itself from the many attacks that have been perpetrated on its soil.”

The report wholly ignored other Somali complaints brought to the mission’s attention: Destruction of telecommunication equipment by the Kenyan army and the Kenyan contingent’s contribution to the enrichment of terrorists – al Shabab – in southern regions.

The Somali government has taken a particular note of this flippancy and blasted the report in a no-holds-barred statement.

“Somalia need not refute this report given the ample evidence publicly available that contradicts its assertions, and the notable witnesses within Kenya that have provided sufficient evidence to the build-up of this belligerent action of desperation by the Kenyan government,” said Somalia’s Foreign Affairs in a statement.

It described the report as “nothing more than a mouthpiece of the Kenyan Government, which neither damages nor deters the (Somali) case, commitment, and determination to ensure these acts of deliberate provocations are held to account.”

When Mogadishu severed its diplomatic relations with Kenya, it accused Nairobi of “constant interference in the internal and political affairs of Somalia.”

But, in a no gentle dig at Somalia’s decision, the report accused Mogadishu of going overboard with its reaction. The report even dismissed Somalia’s allegations without offering a scintilla of evidence.

“The commission considers that these grievances, some of which are longstanding, do not appear to be sufficient to justify a diplomatic separation between Kenya and Somalia,” said the report.

The writers of the report poured scorn on Somalia’s ability to act independently, indirectly questioned its sovereign and openly supported Kenya’s position.

“It is true that the federal government of Somalia is sovereign in its decisions. However, on closer examination,” the report said, “it cannot help but be considered disproportionate and unproductive because the two countries are intimately linked politically, humanely and economically.”

It went on, saying: “The consequences of this measure on the three thousand Somali children attending Kenyan schools on the other side of the border, the hindrance to the functioning of AMISOM which has since been experiencing difficulties in relief operations among Kenyan troops and the economic impact of the embargo on khat in the agricultural region of MERU are a perfect illustration of this.”

Kenya’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs parroted the report, saying it affirmed “the fact that allegations by Somalia against Kenya are wholly unfounded.”

“It is also clear that the decision by the federal government of Somalia to severe diplomatic relations with Kenya was uncalled for,” said the ministry in a statement.

The report lacked details about how its writers spent their time –120 hours — where they stayed while in Kenya and Somalia and the challenges or obstructions they faced from both countries during their investigation. It didn’t explain why the mission met with only two low-level Somali officials and top Kenyan military and diplomatic officials, even though, according to Somalia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, it “agreed to meet with” Somalia’s ministers of defense, aviation and foreign affairs and to pay a visit to Belet Hawo. Nor did it provide any justifications for the mission’s use of Kenyan helicopters when it was expected to have been neutral and independent of any influence by the warring nations.

The Djibouti-led mission was doomed from the start. All but one of its members were Djiboutian, whose President Guelleh has a personal vendetta against Somali President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed Farmajo. The relationship between the two leaders deteriorated after Farmajo in 2018 restored Somalia’s diplomatic ties with Eritrea, Djibouti’s arch foe.

Djibouti feigned shock that Somalia had panned it for bias.

Djibouti has always “strived for peace and stability in the region and made considerable efforts to contribute to the security, stability and peace in Somalia and remains committed to pursuing this endeavor,” said Djiboutian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation.

The anti-Somali report caused uproar and shock among ordinary Somalis, whose country helped Djibouti during its struggle for independence and who considered the tiny nation on the Red Sea as their second country.

The report may have inadvertently peeled back the curtain on President Gulleh’s covert aversion — despite his overt claim to the contrary — to a stable Somalia that can resist insidious foreign interference.

Under Guelleh’s nearly 22-year rule, the campaign to drive non-Issa Somali clans from Djibouti has markedly intensified, a policy that was first begun by France during its colonization.

Critics accuse Guelleh of introducing as a panacea a destructive and discriminative power-sharing model, 4.5, that entrenched Somalis’ differences and prolonged their country’s lawlessness in 2000. Djibouti earns millions of dollars in taxes from Somali businesspeople and their businesses operating in its country.

It’s far from clear why other IGAD member states were not invited to take part in the high-stakes mission that was crucial for the region’s cohesion and stability.

By analyzing the content of the report, one can easily see how the Djibouti-led mission failed to protect its integrity and opted to lap up the Kenyan version, especially when it used Kenyan military choppers to verify the reality on the common border of the two countries.

Expectedly, the result was a report slanted toward Kenya.

“During these overflights, members of the commissions were able to observe Somali military troops massed on the border,” said the report. “The commission was unable to identify an additional camp populated by Somali militias in the overlooked area under control.” The mission didn’t investigate the Kenyan army under the AU mission, referring Somalia’s allegation on the same to the continental body. Many Somalis still view the Kenyan troops in their country as occupiers.

One of the characteristics of the report is its proclivity to jump to conclusions that are not based on any supporting evidence whatsoever.

“The mission considers (charges against Kenyan peacekeepers) unjustified…ostracism against the military forces acting on behalf of amisom,” said the report, a clear attempt to defend the Kenyan force that was accused by the UN in 2013 of facilitating illegal charcoal exports banned by the UN Security Council to choke off one of the terrorists’ main revenues.

Somalia expressed shock and outrage over the report, with its Information Minister Osman Abukar Dubbe accusing the Djibouti-led team that took up the cudgels for Kenya’s position of having an infatuation with Kenya. He called it the “Monica Juma Report,” naming it after Kenya’s defense minister.

“I wish it were written by (Monica Juma) because if she were to write it, she would have shied away from a lot of things,” Dubbe said.

If the report’s aim was to debase and demoralize Somalia to stop it from standing up to Kenya’s violations, it has failed. Somalia’s wrath has since increased; its policies and approaches have become fiercer and more aggressive. It called on the regional bloc to “rescind this frivolous report, and to commission a (new) multinational fact-finding mission.”

If IGAD leaves Somali grievances unaddressed, as it’s likely it will, it’s not hard to imagine what Mogadishu, which said it would “defend its borders by all means necessary,” would do next.

“Somalia reserves the right to seek redress through diplomatic means via the African Union and if necessary the United Nations Security Council,” said Somalia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.