Only genuine housecleaning can cure the ingrained hostilities between Somalia and Ethiopia

President Farmajo and Ethiopian PM Ahmed lost a great opportunity on June 6, when they announced a flawed deal that won’t serve anyone’s interest in the long-term.

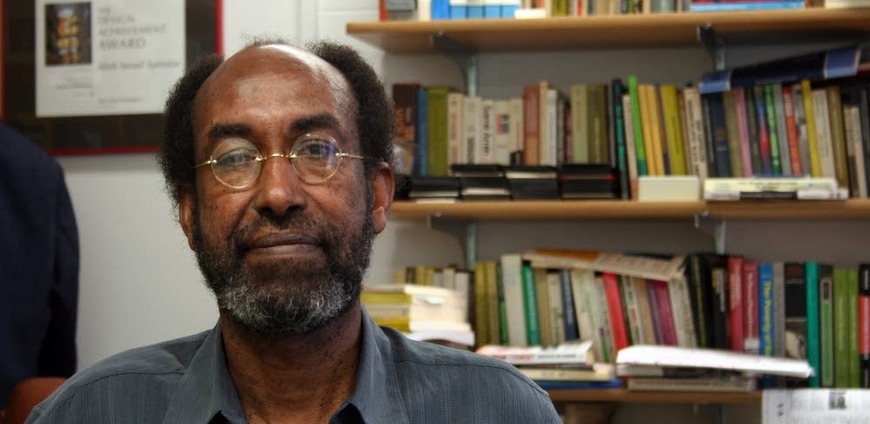

By Prof. Abdi Ismail Samatar

Somalia and Ethiopia have last month announced major security and trade deals that were aimed – according to officials – to renew the two nations’ “commitment to strengthen their brotherly bilateral relations spanning generations.”

In a joint communiqué, President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed “Farmajo” and Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed extolled their relationship, saying that it was “based on shared blood relations, values, history, culture and traditions and espoused by the principles of good neighborliness, mutual respect and promotion of mutual interest.”

Predictably, the hugely flawed agreement has elicited angry reactions from the Somali public who saw it as a part of a larger scheme by Ethiopia to occupy Somalia.

The two countries fought bloody wars that killed tens of thousands of soldiers from both sides, and there are still many thorny issues that remain unresolved, including Ethiopia’s persistent interference in the internal affairs of Somalia and its occupation of the Somali region. Citizens of the two countries also hate each other despite official claims to the contrary.

While Somalis have a raft of sensible reasons to distrust Ethiopia’s new overtures, it’s important to remember that the current antagonism is not in anyone’s interest. The East African region will be much safer if Ahmed and Farmajo-Khayre wipe the slate clean and open a fresh chapter of good neighborliness.

The new Oromo leader, whose people were abused and marginalized by previous Ethiopian governments, has a unique opportunity to be the change agent.

But for any reconciliation to be successful, the two governments must involve their peoples who’ve borne the brunt of the decades-old conflict. Ethiopia has also to publicly apologize for its abuses, occupations, incessant interferences and open sabotage of Somalia’s unity.

Somali and Ethiopian officials are missing out on a great opportunity if they fail to walk gingerly on the failure-strewn reconciliation path or try to airbrush their tragic past out of history.

That past can’t be dismissed by the stroke of a pen. It’s a fact that Ethiopia, which still controls a Somali territory, occupied Somalia in 2006-9 and killed thousands of civilians, especially in Mogadishu, where its forces committed the worst atrocities ever recorded in Somalia’s history.

If Ahmed was bold enough to admit his government’s wrongs against its citizens, he should do the same and accept the consequences of Addis Ababa’s actions in Somalia and ask for forgiveness.

President Farmajo and Prime Minister Ahmed have lost a great opportunity on June 6, when they announced a hurried and unpopular agreement that won’t serve anyone’s interest in the long-term.

Somalis would have felt far more comfortable with their neighbor if Addis Ababa had set a bridle on its hegemonic tendencies and appreciated the reality that Somalis have no desire, even for a second, to be a part of any other country, least of all Ethiopia. The Somali government is committing a grave blunder if it thinks that the Somali public will uncritically consent to its shameful deal with Ethiopia.

Ethiopia should stop talking out of both sides of its mouth: If it’s genuine about having a good relationship with Somalis, it has to halt its interferences in the internal affairs of Somalia, desist from undercutting the central, Mogadishu-based government and sever ties with rogue regional administrators.

To reconcile their people, Farmajo and Abiy have to engage in a genuine housecleaning – root and branch reconciliation.

In his recent visit to Cairo, Ahmed has sworn in front of the camera not to harm Egypt’s share of the Nile water. But having peace with a far-off country is irrelevant when he can’t creatively solve his problems with his immediate neighbors.

Ahmed’s 4-hour agreement with Farmajo has already disheartened many Somalis, who’ve thought that the change of guard in Addis Ababa would lead to a better relationship with Mogadishu. To the dismay of many Somalis, though, Ethiopia’s despicable policies toward Somalia seem not to have changed one little bit.

Ahmed’s reform agenda won’t fly if it fails to be inclusive and holistic. The repressive regime that abused the rights of Ethiopians spared no region, hence the need to appoint a new team of policy experts and rights groups to advise the prime minister on how best he can fix Ethiopia’s Somali problem, not only with Somalis under Addis Ababa’s rule but also with the Somali nation.

Ahmed, who came to power after the Oromo and Ahmara ethnic groups rose up against the Tigranyan tribe’s dictatorship, should be the last to preserve Addis Ababa’s old, abuses-laden policies that miserably failed locally and internationally.

Ethiopians’ hunger for change wasn’t confined to certain regions. It encompassed every part of the country, including Somalis in Jigjiga city who are being humiliated daily by the cruel ruling elite led by Abdi Mohamud Omar, the region’s president.

Prime Minister Ahmed is courting chaos and long term instability for his country if he disregards the voice of the Somalis in Ethiopia or keeps dealing with selfish Somali politicians whose best interest lies in tensions between Mogadishu and Addis Ababa.

Ahmed’s ascension to power presents both risks and opportunities for the two countries.

Opportunities because if he acts independently and adopts different policies toward Somalia, he can herald in a new Somalia-Ethiopia relationship that’s based on mutual trust and cooperation.

Risks because if he continues to think and act like his predecessors who treated Somalia as Ethiopia’s enemy No. 1, he will neither achieve peace nor even the economic integration he’s so obsessed with.

For Ahmed to have a better shot at achieving a long-term peace and good neighborliness with Somalia, he should do three things, quickly and in good spirit.

First, Ethiopia must withdraw all its troops from Somalia, whether they’re under the African Union mission or not. The presence of these forces has always been the source of friction between Addis Ababa and the Somali public. By nature, Somalis don’t like having foreign forces in their country, and that is why al Qaida-linked militants of al Shabab easily target the AU troops in far-flung areas because the continental force lacks the sympathy of the local people.

Respecting the territorial integrity of each nation is crucial for any trust building measures between the two nations that fought vicious wars. Ethiopia can’t continue to keep its forces in Somalia and yet talk about economic and security deals with unpopular Somali elites.

Second, Ethiopia should unequivocally state — in word and deed — that it supports the unity of Somalia. It has to give up all its contacts with rogue Somali politicians and work together with the national government. Prime Minister Ahmed should ditch his policies of inviting Somalis to Addis Ababa and giving them money and weapons to destabilize their country.

Third, Ahmed should end Addis Ababa’s abuses against ethnic Somalis living under its rule. Addis Ababa can’t aspire to build a strong and prosperous nation while trampling on the rights of Somalis in the Somali region.

Addis Ababa’s unilateral decision to start the production of oil in the Somali region without consulting broadly with all stakeholders will only lead to disasters in the long run. Addis Ababa should publish its agreement with the Chinese company, Poly-GCL Petroleum Investment Limited, so as the local Somalis know their share of their oil. Without a clear revenue sharing agreement, the oil bonanza can turn into a curse.

Now, one may ask what, then, can Somalia offer to Ethiopia, a landlocked nation that is concerned about Somalis’ claim on the Somali region and desperately needs an access to the Horn of Africa nation’s seas.

Somalia can give Ethiopia sustainable peace. By reconciling with Somali, Ethiopia will have a neighbor that can come to its aid when it’s in distress.

In 1963, Ethiopia’s Halile Selassie sent a cable to then Somalia’s President Aden Abdullah Osman, asking for Mogadishu’s support for Addis Ababa’s bid to host the Organization of African Unity headquarters. Unlike the current administration in Mogadishu, Osman forwarded the cable to Prime Minister Abdirashid Ali sharmarke, who approved Somalia’s vote for Ethiopia.

Without that vote, Ethiopia wouldn’t have had today the continental body’s headquarters in its capital.

Also, a strong and peaceful Somalia that is a friend of Ethiopia can play a crucial role in creating a powerful East African community whose voice is respected not only in Africa but in other international forums.

Farmajo and Ahmed still have an opportunity to honestly resolve their two peoples’ differences, but Ethiopia should take that first, bold step toward this long journey of reconciliation and say sorry to Somalis.

But if Ethiopia — always suffering from terrible delusions of grandeur — continues to whitewash the past and tries to strike deals with a few individuals as it usually did in the last two decades, it would be the loser in the long run. Ethiopia can tempt a few sellouts, but it won’t ever be able to buy off doughty Somalis who are determined to defend their country.

Samatar is a professor of Geography at the University of Minnesota and research fellow at the University of Pretoria, South Africa. He can be reached at samat001@umn.edu